FORT COLLINS, Colo. — Over three days in early February, farmers, ranchers, researchers and businesspeople found common ground in the San Luis Valley around the region’s top crop: the potato.

Spuds weren’t the only topic of discussion at the 41st annual Southern Rocky Mountain Agriculture Conference, hosted by Colorado State University Extension, but they were front and center, along with water scarcity, soil health, potato diseases, fertilizer, pesticides and livestock.

Those who have only passed through the San Luis Valley to visit the Great Sand Dunes might not realize that 25% of fresh market potatoes in the U.S. are grown there. The region is second only to Idaho in producing fresh market potatoes, which includes those sold to grocery stores, restaurants and institutions like schools.

What makes the Valley a potato powerhouse?

“Potatoes like sunny, cool days and warmer nights, and we have all that,” said Jim Ehrlich, executive director of the Colorado Potato Administrative Committee.

CPAC is funded by and supports local growers through quality standards, sustainability best practices, research, marketing and market tracking. CPAC works with growers to determine their research priorities and funds work by CSU researchers.

“Last year we spent $380,000 on research projects,” Ehrlich said. “It’s mostly potato-grower money that we funnel back to CSU so they can work on problems that growers have that help them stay profitable, be more sustainable and have a better business model.”

CSU’s San Luis Valley Research Center does a lot of that research, including studies on potato breeding and selection, pathology, crop management and field physiology, post-harvest physiology, and seed certification.

Built on ag

Agriculture is the economic driver of the Valley, and water is the No. 1 concern. The research center has been working on ways to better manage a shrinking water supply. Thanks to CPAC funding, the center recently upgraded the CoAgMET agricultural weather stations in the Valley.

With the upgrades, “we get more real-time data, and farmers can make more accurate applications of water,” said Zach Czarnecki, manager of the research center farm and co-organizer of the conference.

Another ongoing project at the research farm is evaluating alternative crops for viable options that farmers can add to their rotations that will save water but also make money.

Potatoes aren’t the only crop that thrives in the Valley’s mild temperatures, ample sunshine, fertile soil and precision irrigation.

“You can grow probably the best barley in the country in this area in terms of yield; our climate is just so suited for it,” Czarnecki said. “At the research farm, we’ve been partners with Coors for 65 years.”

For every six-pack of Coors, one can’s worth of barley comes from the San Luis Valley, he said.

While potatoes followed by barley are the highest value crops in the region, alfalfa occupies the most acreage.

Czarnecki and the four research scientists based at the center work closely with the region’s agricultural community to understand what they need.

“The most valuable thing you can do is work with your neighbors and your constituents because that’s who we’re serving,” Czarnecki said.

Working toward the same goals

The annual ag conference provides a forum where researchers, ag producers and businesses can share their results and new practices and technologies.

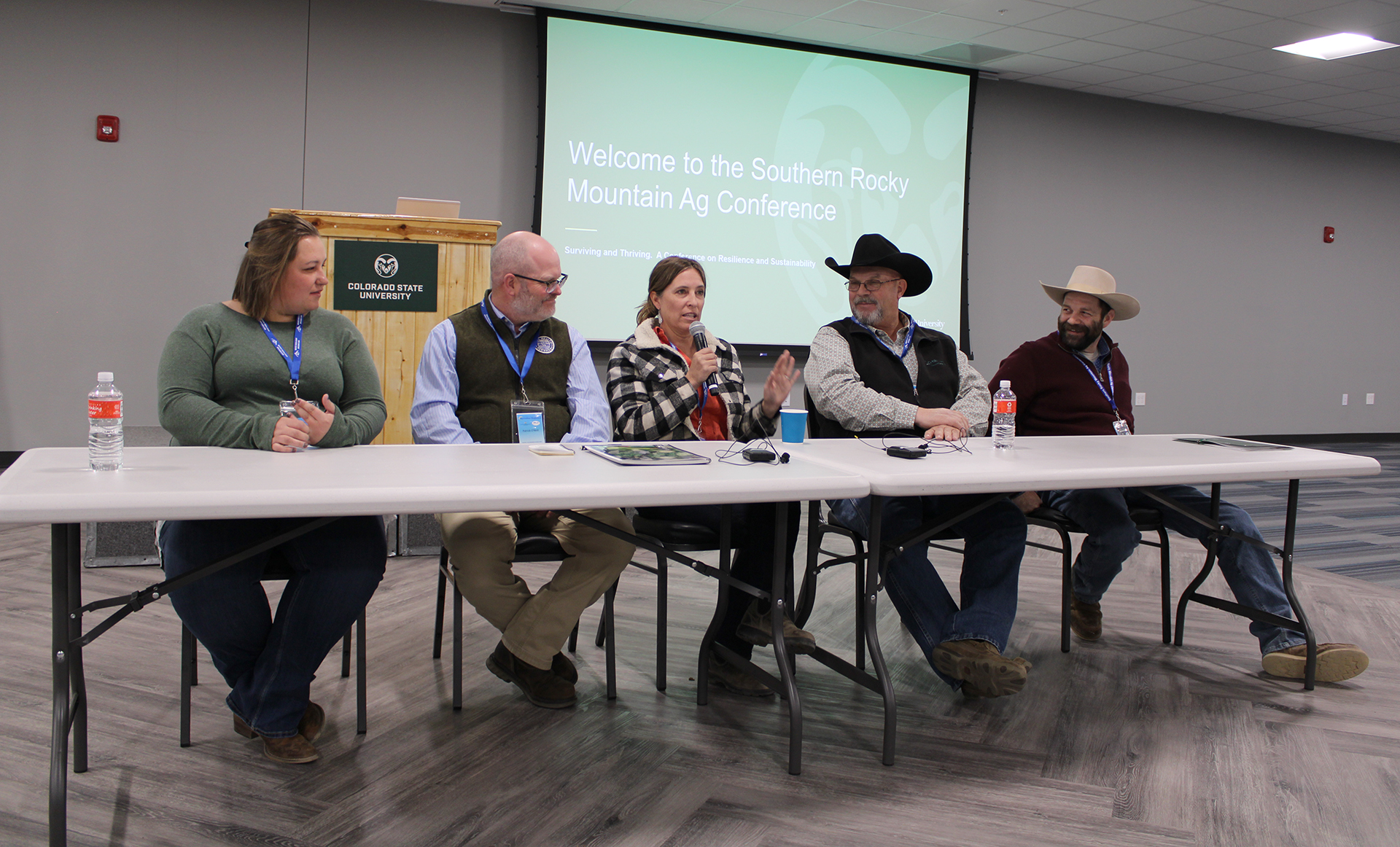

On Day 2 of the conference, a panel of soil health experts convened to discuss methods they had tried and their findings. The panel consisted of two local farmers, a rancher from the Oklahoma Conservation Commission, a local crop consultant and a CSU Extension regional range specialist. Each panelist was also a researcher in their own right who drew on generations of experience caring for the land to answer audience questions.

Among the five panelists, they had tried many strategies, including cover crops and forage crops with grazing to improve soil and reduce fertilizer and water usage. Jimmy Emmons, the Oklahoma cattleman who was also the conference keynote speaker, even put a GoPro camera on a heifer to learn more about how cattle select forage.

“Not everything I do works,” Emmons said, but the cow-cam experiment offered valuable insights into how his 15-species grazing mix was received.

All the panelists expect more change to come.

“The way we view it is if we’re not changing and adapting to the times, we’re not going to last,” said panelist Erin Nissen, a fourth-generation potato farmer in the San Luis Valley. “Our farm’s been through some dry, tough times, but our farm has never been the same, from my great-grandparents to my dad’s parents to us. Our view is if we can build our soil up and treat all the resources we use – soil, water, land, community – as good as we can, that will make us successful.”

Two-way street

Annie Overlin, a CSU Extension regional range specialist, shared insights from her work as part of the panel. Overlin, who is a sixth-generation rancher, described her job with Extension as a bridge to connect the agricultural community with the information they need and experts that can help.

“Extension is special in that we live and work in the same communities with our producers,” she said. “So it’s kind of natural, you’re just hanging out with your neighbors.”

Overlin visits ranches and facilitates discussions to find out what producers need. Based on the ranchers’ input, they are figuring out the research they would like to focus on with the help of CSU’s scientists.

“Extension has this role of not being the expert but more of an interpreter and facilitator,” Overlin said. “In order to facilitate a conversation, it’s important to create a dynamic where you’ve got a real two-way street.”

The conference was one example of Extension facilitating conversations and bringing together campus and community partners, so everyone could learn from each other.

— Jayme DeLoss, Colorado State University